|

Being a first-time author is full of surprises, some good and some...not so much. An example of the former would be my first 5-star review on Amazon, about a month after The Job To Be Done was published (thank you Dave!). An example of the latter would no doubt be my first email pointing out a factual error in the text. Oh boy, that stung! The manuscript went through multiple rounds of editing, fact checking and proof reading, but somehow some clangers got through. I was so proud of all the meticulous research I had done, checking and rechecking my facts, but you know what they say about pride, and where it goeth....

The first mistake that was pointed out to me is on page 74 of the hardcover edition – the first 1,000 bomber raid of the war was, of course, in 1942 not 1943. A few more rolled in over the course of the next few months, as more people read the book. My eagle-eyed brother Stu pointed out that my story of Bob McWhirter’s trip home after his time overseas contained some sloppy geography. On page 211 I relate that Bob arrived in Montreal and then took a train East home to Prince Albert – he, of course, travelled west. I tried to fake my older brother out by replying that Prince Albert was moved to it’s present location in the 1950’s, but he didn’t fall for it.... Another error is repeated twice (on page 43 and 44), where I label the Personnel Reception Centre in Bournemouth a “receiving centre” by mistake. I have saved the worst and most embarrassing for last. A kind reader recently contacted me via this website to tactfully point out that the Prime Minister of Canada during the Second World War was William Lyon McKenzie King, not Lester Pearson (page 10)! Ouch. I have gathered all the errors, tiny and not so tiny, on an errata sheet that at present totals ten items. When I am sure I have them all, I hope to publish a second edition of the book, with the corrections made. And my advice to any aspiring non-fiction writers out there is that you can never do too much fact-checking, preferably before publishing!

0 Comments

One of the many things that surprised and impressed me during my research into my Dad’s air force experience was the training he (and all the tens of thousands of his comrades) received. From the day he joined the RCAF to the day he left Gransden Lodge after completing two tours of combat operations (almost three years later), it never ceased. What particularly impressed more than anything else was what I will call the sincerity of the training – every effort was made to make the training relevant, clear and focused on real-life situations. I couldn’t help but contrast this sincere effort to some of the “C.Y.A.” training courses I was required to complete during my time with B.C. Corrections – more on this in a bit.

Dad’s training started at Manning Depot in May of 1942 with rifle drill, learning to break down, clean, reassemble and then accurately aim and fire the Lee-Enfield .303, the basic rifle of the British forces in the Second World War. His final bit of training, in September of 1944, was an air-to-air firing and fighter affiliation flight in a Lancaster bomber. In between those dates the training never ceased – dinghy drill, parachute drill, Standard Beam Approach flights, H2S (“Y Runs”) navigation flights, cross-country mock-bombing exercises etc etc. One of the most innovative methods used by the RAF to train their airmen was a small, flimsy and innocent-looking magazine called TEE EMM (from Training Memorandum). It was provided to aircrew around the world in their various theatres of war, but was mainly focused on Bomber Command operations based in the U.K. Over the course of a year or so, I managed to obtain seven original copies of TEE EMM via eBay, covering the months Dad and crew were flying operations in 1944 - I wanted to read what they had read. TEE EMM turned out to be a fun and informative read, which used a light-hearted approach to tackle deadly serious issues. Those who wrote the articles knew that their audience was (for the most part) young men barely out of school, and wisely tailored their approach to connect with them. Consisting of short articles, anecdotes, photo illustrations and cartoons, each issue of TEE EMM was a smorgasbord of pertinent information, dished up in digestible portions. Some examples : A photo gallery identifying the various United States Army Air Forces uniform wings in use at the time. A short article explaining the deadly consequences of the common practice of diving an aircraft to put out an engine fire. A humorous poem to address a serious issue: aircrew who baled out of a stricken aircraft but forgot to pull the ripcord of their parachute until it was too late – it did happen, despite all their training. A plea to take care of the paper maps issued to aircrew – too many were wasted and precious resources were used up to replace them. An article for air gunners discussing the value and the limitations of tracer fire, and an article for pilots on techniques for landing if you have no ailerons (spoiler alert: it can be done!). A redacted copy of a telegram reporting a fatal crash – a young fighter pilot in training decided to show off his new Spitfire to his proud family and flew low over their home. In a tragic split second moment of inattention he slammed into a nearby hillside, killing himself in front of his parents and sister. No commentary accompanies the telegram: the tragic dangers of horsing around speak for themselves. One character who populates every issue of TEE EMM is P.O. Prune, a lovable but thoroughly incompetent and completely clueless cartoon pilot. Prune does everything wrong, but has more lives than a cat, walking away from every crash unscathed and in the process showing aircrew what not to do! My very favourite Prune cartoon depicts him flying at night, clueless as to where he is. There are searchlights and flak bursting around his cockpit (helpfully labelled with swastikas!) but Prune is nonplussed: “My, Southhampton seems pretty jumpy tonight!” Despite the stellar job TEE EMM did in teaching airmen it wasn’t without it’s missteps: in 1943 an anonymous pilot wrote an article suggesting that to avoid the German flak, bomber pilots should change course every 30 seconds as they approached the target. Sir Arthur Harris, commander of the force, blew a gasket, and said such “idiotic antics” would lead to inaccurate bombing and threatened to have TEE EMM banned from his bomber squadrons. TEE EMM backed down and agreed in future to have articles vetted before publishing. I can’t help but contrast all this sincere effort with the kind of training I often received during my time with the Corrections Branch. As the years went on and pressures to save money increased, the training deteriorated to the point when it consisted almost entirely of online reading. The staff, completely unengaged, would sit in front of a computer and quickly scroll through the pages, most not even reading them, until the last page, when they would sign with their employee number to show they had completed the “training”. The main point of all this seemed to be to protect the employer – if any situation went sideways the front line staff could be blamed and proof could be shown that they had been well “trained” and should have done things differently than they did. I always thought that the many keen young men and women I worked with deserved a better effort from their employer, and my research into Bomber Command’s training proved to me that it could be done. Spoiler alert: yes, I think the young men of Bomber Command were heroes – but let’s dig into it a bit and explore the concept of heroism...

Personally, I find that the word “hero” is a loaded one, and is one that we have overused to the point that it is in danger of becoming meaningless unless we are more careful in applying it. For example, after 9/11 it seemed everyone in uniform was suddenly a “hero” – I remember reading about a bus driver in Toronto who was deemed a hero for braking their streetcar in time to avoid hitting a stray toddler. Really? I have heard blood donors being referred to as “everyday heroes” - frankly, the hyperbole becomes numbing after a while. I remember the wonderful Pixar movie The Incredibles, where the evil genius, who has a jealous hatred of the Superheroes, creates tech that allows anyone to do the things that before only the “Supers” could do. His end game? “When everyone is a hero, then no one is a hero!” (Cue evil laughter). I butted up against this concept of “hero” (often the code word “peace officer” was substituted in my workplace) many times during my time working for the Corrections Branch. Although working in a prison requires diligence, professionalism and courage, I found that some of my co-worker’s constant attempts to equate us with police officers (or even the military) were, in my view, embarrassing to us and disrespectful to police officers, who really did put their lives on the line when they went to work. It seemed to me that some of these efforts to artificially raise the status of Corrections staff to “heroes” amounted to puffery (what the airmen of Bomber Command would have referred to as “shooting a line”, a cardinal sin to them) and to me it was a sign of a kind of group insecurity – in my mind, we should have been proud of the work we did, and not attempt to ride on the coattails of the police or military, trying to bask in some of their reflected glory or status. So, you ask, what is a real hero? Well, over the years I came up with two criteria that, in my mind, had to be met to fit the bill. 1) A hero would have to put their own life at risk to save another. Returning a lost wallet or pulling an errant child away from a balcony railing is not heroic, it is just being a decent human being. 2) A hero would need to be unprepared and untrained for the specific task. Sorry firefighters, but you are trained, paid, equipped and well-prepared for what you do, you are not heroes. And I bet most of you would agree with me - you are professionals and I have the utmost respect for you and what you do for a living. So, how do the young airmen of Bomber Command stack up against these two criteria? Well, I know for a fact that none of them would describe themselves as heroes – I have heard more than one WW2 veteran insist that the real heroes were the ones who didn’t come home. But regardless, I will throw my opinion into the ring. There is certainly no question that they put their lives on the line – Bomber Command losses ran at 50%, and that is not counting the thousands who died in training accidents. Was their sacrifice to the benefit of others? I would argue yes. The breadth of Nazi savagery in WW2 is breathtaking and almost beyond comprehension. The well-documented extermination camps were just part of the Nazi murder machine – in far-flung parts of the Nazi empire, from the Greek islands to Ukrainian and Polish farms, to camps for Soviet P.O.W.s, to French and Norwegian villages the Wehrmacht and SS shot, starved, gassed and bludgeoned to death untold tens of thousands. Every day the war lasted, the slaughter of innocents went on. The “bomber boys” played a large role in ending the war as quickly as possible and finally bringing the madness to an end. But weren’t the boys of Bomber Command prepared and trained for what they did? I would argue not. As I explained in The Job To Be Done, I don’t think the technical training that aircrew received in their respective tasks (navigating, flying an airplane, operating a wireless set etc) in any way prepared them for the horrors and terror, night after night, of their kind of war. Only camaraderie, commitment to the fight against Hitler and pure courage sustained them. Yes, they were heroes, and we would do well to use the term more carefully, lest we diminish its power to inspire us. I have mentioned in The Job To Be Done how often I got “sidetracked” during my research, spending time digging into some arcane subject (like food rationing in wartime Britain, or types of uniforms worn by Bomber Command airmen) that had piqued my interest. One such subject was the autopilot, universally known to aircrew as “George” for some reason, a device almost all RAF aircraft were equipped with.

I was fascinated by the actual technology of the device (in WW2 a brilliant system involving gyroscopes) as well as being intrigued by possibilities of when it would actually be of use! I mean, I could picture its usefulness in peacetime, on a long trans-Atlantic flight perhaps, but in a combat situation....? I will tell three stories that will illustrate the range of uses that “George” was put to...or was allegedly put to I should say... At one end of the scale is a memory I have of my Dad talking about the autopilot – he was adamant that he never used it. He told me that his attitude was that in the precious few seconds it would take to disengage “George” (assuming you were in the pilot’s seat, never mind in the cockpit....) and take control, he and his crew could be shot out of the sky and killed. Responding to a night fighter attack required instantaneous action. He had a similar attitude towards another “helper” offered, “wakey-wakey” pills, a type of amphetamine tablet handed out to those aircrew who wanted it by the Medical Officer before operations to increase alertness and wakefulness. Dad told me he could never understand how anyone could get sleepy or distracted while every night fighter and flak gun in Europe was trying to kill him. The second story is on the middle of the scale: one aircrew memoir I read during my research related that the writer’s skipper (pilot) would sometimes engage the autopilot without telling the crew, and then wander through the aircraft front to back, visiting each of his startled crewmates in turn. Plausible I suppose, given the right set of circumstances... The final story is one that beggars belief in my opinion. In the unpublished memoirs of an RAF tail gunner, shared with me by his daughter, he states that after dropping supplies to the French resistance he and his crew would head their Halifax bomber back to their base in North Africa. During the long trip back across the Mediterranean Ocean his pilot would sometimes engage George and they would all take a nap. Perhaps the story got “embellished” over time – I have certainly run across that phenomenon over the years, and likely engaged in it myself on occasion! I remember a yarn I heard when I was travelling through the U.K. in 1982 that illustrates this. I was travelling by bicycle and had met another young Canadian who was backpacking – we decided to have a pint in the local pub. We were soon joined by what I would have described at the time as an “aging hippie”, an Englishman who regaled us with stories of his National Service days flying as part of a Shackleton (a four-engined maritime patrol aircraft) crew in the RAF. We were then joined by yet another pony-tailed elder who had overheard our conversation about flying. He too had spent his National Service time with an RAF aircrew in the 60’s. The two “seniors” began swapping stories, and at one point one asked the other “Did you ever let your pilot fly sober?”. The other fellow feigned shock: “God no!....well, actually, we did once, but he nearly killed us, so we gave him a bottle part way through and he was fine after that.” I remember telling my Dad this story when I got home from Europe – he wouldn’t even dignify the tall tale with a comment, he merely rolled his eyes and shook his head! I spent about 25 years in jail.

Well, to clarify, it was in 8 to 16 hour instalments, and I was being paid to be there. I was hired in 1999 as a Security Officer at a maximum security B.C. provincial correctional centre and over the next two decades spent countless hours supervising various prison living units (a sort of self-contained pod of 18 to 38 inmates). I have dealt with untold numbers of young men leading broken, pitiful lives during the time I spent as a Correctional Officer. Over the years I have often been asked by friends and family if there was some single factor that led to these lives being wasted in jail. As an aside, don’t let anyone con you into believing prison is about rehabilitation – it is little more than a warehouse. It at least allows offenders an opportunity to get clean and do some serious thinking about the direction of their lives, but there is no situation I can think of that proves the old saying “you can lead a horse to water but you can’t make him drink” than a criminal serving time in prison. Mind you, the powers-that-be in charge of the prison don’t help much – what sort of facility that is supposedly focused on rehabilitation has no library, but does put colour TVs (and 24/7 satellite TV service) into every cell? As far as the reasons that young people end up in such a dead end, for a long time I felt that the underlying factor was almost always drugs. The men I dealt with very often told me they were either on drugs when they offended, committed crimes to pay for drugs, or were involved in the drug trade, even if they didn’t “use” themselves. I accepted this answer for years, but slowly I realized that this answer begged a question – why did they turn to drugs and gangs in the first place? A new, more profound answer presented itself – most of these young men lacked any kind of father figure in their lives. The best that many could hope for was a string of abusive stepfathers or mom’s boyfriends. One young man, not even out of his teens, told me about the time his stepfather shot his dog in front of him to punish the boy – little wonder the boy turned to drugs to ease the anguish in his life. As I researched my Dad’s time in the RCAF and spoke to the sons and daughters of his crewmates, I began to realize how fortunate we had been to have men of character in our lives, mentoring, guiding and setting an example. I vividly remember an incident that occurred when I was about 16, working after school in Dad’s small business, an appliance repair shop. One of our repairmen, a young man named Ron, who I looked up to, died in a sad drowning accident. A few days after we got the news, Dad asked me to help him pack up Ron’s tools. As we sorted and packed Ron’s toolbox, Dad quietly commented “You know son, this will probably be a painful package for Ron’s Mom and Dad to get, but it is the right thing to do – these tools aren’t ours, they belong to his family now.” Lessons like that stick with you, and although I know it will sound hopelessly old fashioned, a boy needs a father to teach them. One day at work a fellow Correctional Supervisor (I will call him Dan) and I were discussing our shift’s daily staff compliment. I reminded him that one of our Correctional Officers was off for the day, having taken a special leave day due to his father passing away. Dan was dismissive: “why would you waste a special leave day for that? ... if someone called me and told me my old man was dead I would tell them not to bother me at work. I couldn’t care less”. I was shocked, but I kept it to myself – but it sure brought home to me that not everyone is fortunate enough to have a man worthy of being looked up to as a father. More that once I have pondered the fact that every family member of my Dad’s crewmates that I contacted respected and revered their fathers without exception....is that just a coincidence, or was author Tom Brokaw right in calling them “The Greatest Generation”? During my time researching my Dad’s time in the RCAF, I read about a wide variety of subjects, from Atlantic convoys to tank warfare on the Russian front, from Nachtjaeger squadrons in France to the building of airfields on the Canadian prairie. One character popped up at every location and situation I read about: the animal.

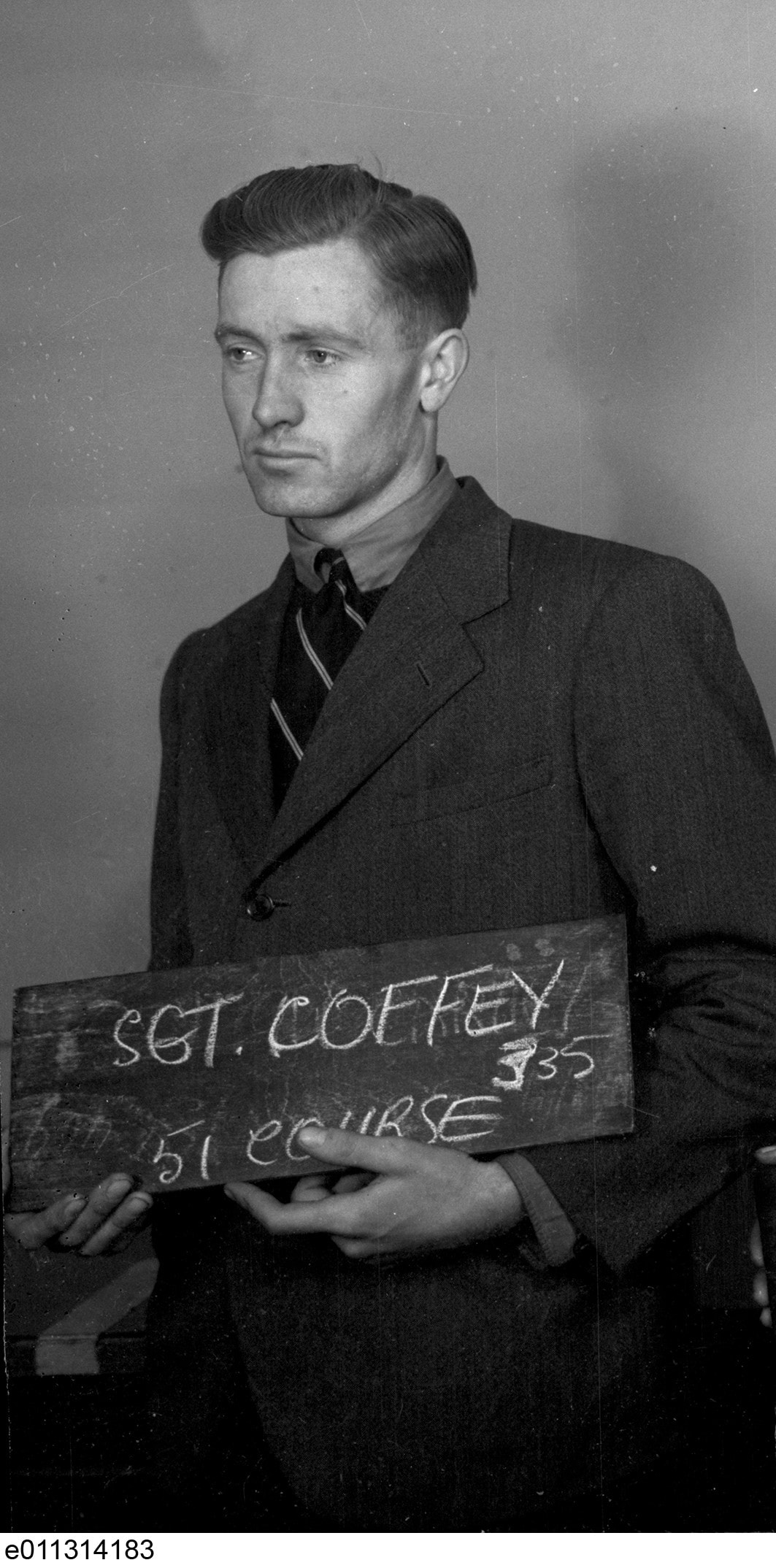

Innocent animals have always been caught up in the human insanity we call war, whether pressed into servitude, caught in the crossfire as their habitats became battlefields or kept as companions. WW2 was no different, and from cats on battleships, dogs on guard duty, horses pulling artillery (the German army used in excess of 3,000,000 horses from 1939-45) to pigeons flying messages, animals were there in the front lines. Bomber Command made use of homing pigeons until early 1944, and all aircrew took a pair of them in a cage on every operation, usually in the care of the Wireless Operator. If they had to ditch in the North Sea, a message with their location would be tied to the leg of the birds and they would be sent on their way. A surprising number of aircrew were rescued from near certain-deaths by these humble birds. The British even had a medal for brave animals, the Dicken Medal, which was awarded to heroic deeds by dogs, pigeons and horses (and a single cat, in 1949.) One of my favourite stories from WW2 is from the wonderful (and not widely known) book Six War Years by Barry Broadfoot. Broadfoot travelled Canada in the 1970s, sticking a microphone into stranger’s faces and asking simply “what did you do in the war?” The stories cover everything from being a kid on the home front to harrowing memories of combat in places like Italy and Normandy and are transcribed almost verbatim, without commentary. The story I recall so fondly took place in the middle of the North Atlantic. An unarmed repair ship itself broke down halfway to England and the convoy it was part of had to leave it behind. While the small crew worked frantically to fix the problem so they could try to catch up, the conning tower of a German U Boat suddenly broke the surface of the ocean not far away. Much to the crew’s amazement, the hatch opened, a dingy was inflated and several German sailors began to row the short distance towards them. When the dingy came alongside, the captain of the repair ship was astonished to see that the German officer in the dingy was holding a large fluffy cat. “The captain of our submarine wishes to know if you might have some milk for his cat?” asked the officer. The captain of the repair ship immediately sent one of his men below to the galley to fetch some condensed milk. A net bag with several cans was duly passed to the German officer, who gave his thanks and had his men row back to the U Boat, which then peacefully submerged and went on its way... Apparently the Coffey crew, in Tholthorpe in the spring of 1944, shared their home with a small menagerie of birds and animals. The 420 Squadron Operational Records Book notes on May 29th, 1944 that “...the Squadron is getting to look like a zoo more and more every day. The following is the strength of pets: 1 fox, 2 dogs, 3 cats, 2 rabbits, 8 ducks 2 geese and one hen.” The entry appears lighthearted, but it doesn’t have a happy ending, and it continues: “...the killing order was given. Now the old hen lies well roasted on its back in the Officers Mess kitchen to be devoured at noon. No more eggs for the batman!” War is hell, as they say.  Six tiny black and white “headshot” photos of my Dad have, in an odd way, bracketed my time as the temporary caretaker of my Dad’s WW2 memorabilia. Four I inherited in 1990 (shown above) when Dad passed away and two arrived in my email inbox just last week, just days after The Job To Be Done was finally published. These mugshots, taken around the same time and location, and for the same purpose, took eighty years to be reunited in my files. The two I received recently I had worked hard for – I had seen the tiny 35mm negatives among the hundreds of pages of scanned documents that the Canadian government had sent me when I requested Dad’s service records. Only the negatives were shown – I could tell they were of a man in civilian clothing, but I would not have known for sure it was Dad if he hadn’t been holding a sign, helpfully reading “COFFEY”. See below. At any rate, a year or two after first seeing the negatives, I decided to ask the Library and Archives Canada if it would be possible to get them developed and sent to me. It turned out that it was, although due to the Covid pandemic the bureaucratic wheels turned very slowly. They finally arrived last week, and they are delightful. All six of the photos are examples of escape and evasion photos. You can see in one that the chalkboard Dad holds says “51 Course” - this indicates it was taken at the No.22 Operational Training Unit, which Dad and crew attended in September 1943. During the course of the War, hundreds of allied aircrew who had been shot down were able to evade capture, connect with the local resistance and eventually make their way back to England. The numbers were small compared to those who were killed or captured, but it is still an amazing story. To improve the chances of those who found themselves alone in enemy territory, each airman was issued with a pocket-sized escape kit. This usually consisted of items like silk maps, chocolate bars, a tiny compass, some Benzedrine tablets (“wakey-wakey pills”) to boost energy, some local currency and a set of tiny passport-style photos, taken in civilian clothing. Should a downed airman be lucky enough to make contact with the local underground, this last item could be used by their experts to make fake identity papers. My Dad looks exhausted in all the photos, especially in the one I just received. It’s not surprising: by September of 1943 when the photo was taken, he had been undergoing near-constant (and often dangerous) training for over a year. He had said goodbye to his family, not knowing whether he would ever see them or Canada again. He had crossed the ocean to a faraway land, without a friend, and had been posted into one strange, challenging environment after another. It is no wonder there are bags under his eyes! As always, thank you for reading. Two of the oddest items in the box of wartime memorabilia that I inherited from my Dad in 1994 were the pair of red plastic hearts you can see below. Dad had never shown them to me, so I had no idea what their origin was – they seemed so incongruously cute sitting among the pieces of flak shell, dog tags and medals in the cardboard box. It took a few years for me to get around finally to trying to decode their meaning, and it is a touching story. The two hearts are examples of what was termed “sweetheart jewellery”, a common wartime form of (often) homemade trinket, meant to be sent home to wives and “sweethearts”. You can find a wide variety of examples for sale on eBay (which I admit I find rather sad...they meant a lot to someone at some point). During WW2 the British government frowned on jewellery production, as it was considered a waste of resources. However, it seems they turned a blind eye on whoever crafted the tiny silver wings that you can see embedded in the red perspex. The red material was likely salvaged from the navigation lights of a crashed airplane, the hearts then crafted by resourceful ground crew into the finished pendant, and sold to aircrew for them to mail home to loved ones far away. The pendants are just one example of many different kinds of decorative trinkets made during wartime from salvaged material – in WW1 they were known as “trench art” and often made from brass shell casings. I have no idea when or how my Dad sent these home to my Mom....were they both for her, sent at two different times? Or were they sent at the same time, one for his “sweetheart” and one for his son, baby Gary. After I found out a bit of the story behind the trinkets, I had them framed, along with my favourite picture of Mom and Dad, taken just before he shipped overseas in 1943.

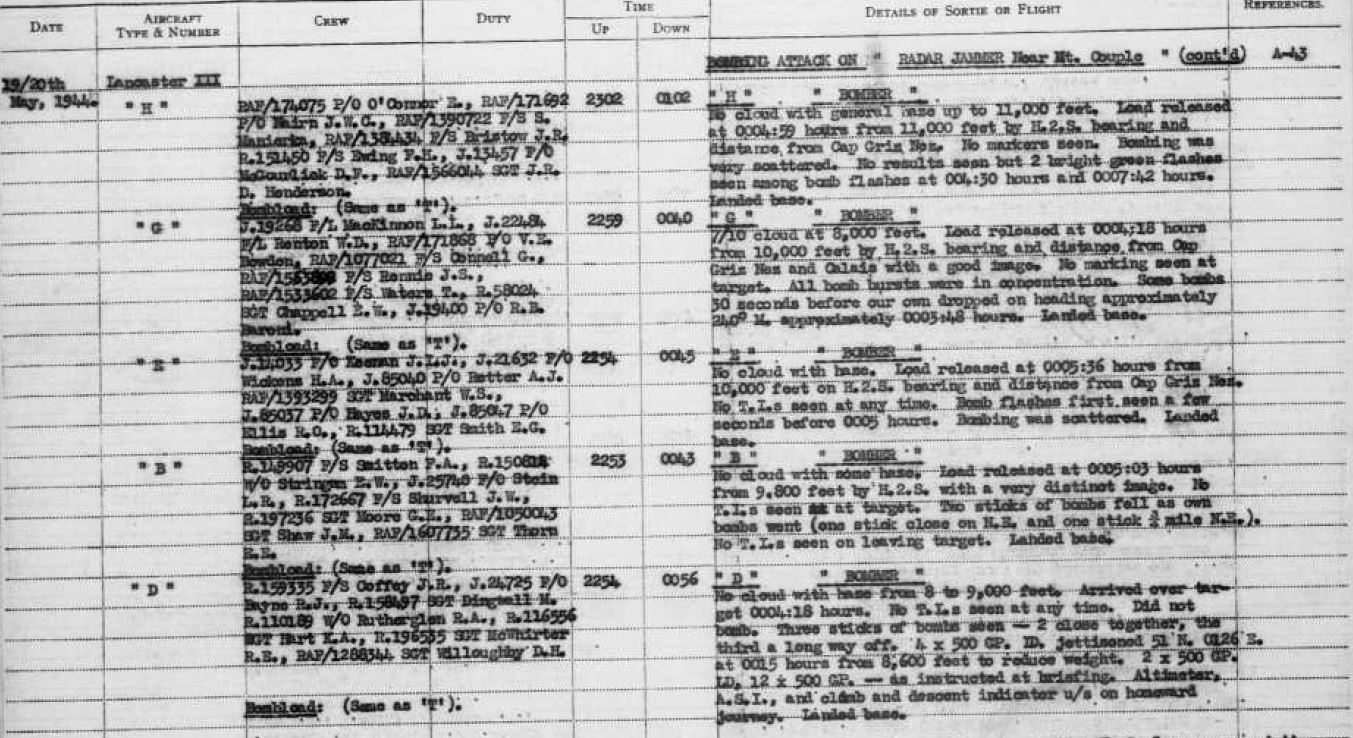

Thanks for reading! The final countdown until The Job To Be Done is at last published has begun - I hope to have my hands on some copies and see it available in online bookstores in the next few weeks!  As I look back over the past 7 or so years of writing a book that I never intended to write, I often ponder the skills I learned while delving into to story of my Dad and his crew. I have always been a bit of a Luddite – modern technology often seemed to me to promise more than it delivered (and to sometimes bring nasty and unexpected pitfalls), and I still feel that way about social media. But there is no doubt that without the internet, this book could never have been written. The resources available today online mean that anyone can bring to bear research power that would boggle the mind of a scholar, a whole department of scholars, only 30 years ago. I can still recall my amazement and delight when I opened up a document I had downloaded from the U.K. National Archives and saw the original Bomber Command squadron records detailing that night’s raid. My Dad and his crewmates were each listed, and what they had seen and experienced was detailed, often in their own words (see an example above). This was real history, and it thrilled me! Similar discoveries awaited me as I honed my research skills through trial and error, and by watching YouTube tutorials. Online forums proved invaluable – I joined a community of curious researchers who valued the past as much as I did. We helped each other whenever we could in our individual areas of interest. Then there was eBay. I decided to try and find and purchase some original WW2 documents and photographs rather than just download “stock” images to illustrate The Job to be Done. Bidding on eBay turned out to be another skill I needed to learn, and at the beginning, I was often “sniped” at the last second by bidders using purchased software to assist them in the bidding process. Over time, however, I gained skills, and ended up acquiring some amazing original photos and documents, including an autographed card from Sir Arthur Harris. Writing itself was a skill that required honing. I have been a voracious reader all my life, and I aspired to write as well as my favourite military history writers, people like Robin Neillands and Martin Middlebrook. No, I don’t feel I reached anywhere near that level, but a wise man once told me that goals are like the North Star – you can walk for a hundred years and you will never reach it, but if you keep it in sight you will always be sure you are going the right direction. It was often hard work – I am positive that every paragraph in The Job to be Done was written and re-written at least half a dozen times over the years. But often the words just flowed and I am convinced this is because I felt so passionate about the subject – it was a labour of love and I put my heart into it. I think the point I am trying to make with all this is that the days are gone when you had to have a degree or some sort of professional training to dig into history! If you are curious about someone in your family’s past, then there are resources out there that will allow you to delve into it. Don’t be intimidated, if I can do it, anyone can. I am willing to wager that there is an ancestor in your family tree whose story is waiting to be told. You might not end up writing a book, but I promise you will make some thrilling discoveries, and learn new skills in the process! If I can offer any advice or pointers, please reach out, I would be glad to help. Thanks for reading! Welcome to the first blog post of the Job To Be Done website, and thank you for visiting the site and for taking the time to read the blog! It is now the end of 2022, and I am looking back down the road that I started travelling so naively in 2014. As I have related in the book, the idea of writing a book didn’t even enter my mind when I started researching my Dad’s logbook 8 years ago....the project seemed to have a life of its own, and grew like Jack’s proverbial beanstalk until it took over a good portion of my life. Back in 2014, I was a Correctional Officer, working at a maximum security provincial jail in Maple Ridge – I was considered a “senior staff”, having about 15 years of experience at that point, and often worked as an acting Supervisor. It was, and is, a tough way to make a living – my coworkers and I faced (and they continue to face) a grindingly negative environment with little or no support, appreciation or recognition from our management or employer. By the time I retired in January of 2022 morale was rock bottom and employee turnover was sky high – it is truly a shame that a job that is so vital for society and so personally challenging is so poorly appreciated by the public or the employer. But I digress... Finding the time to research and write while working shift work was challenging, but in 2018 I won a promotion to full-time Correctional Supervisor and soon found a post with a regular Monday-to-Friday dayshift pattern. With regular “normal” hours, I soon developed the habit of rising early each workday and spending an hour working on the book before heading off to jail for the day. On the weekends I would set aside two hours or so each day to research, write and rewrite. Slowly but surely the manuscript expanded and I grew increasingly confident with what I was producing. At one point I reached out to my co-workers in the B.C. Public Service via the online employee newsletter and explained my project and asked for any stories they might have about family members who might have served in Bomber Command – the response was remarkable. Stories poured into my inbox from people all over British Columbia, and it showed me that there was enthusiastic interest in the story I was trying to tell. Some of the stories shared involved other branches of service, like the army or navy, but the family's pride in their fathers, uncles and grandfathers who served was palpable in each of them. The response also presented a problem: I had asked others for their stories, but I could see from their volume and variety that the book would never be finished if I didn’t maintain a razor focus on telling just one, that of the Coffey crew. So the stories I was told became an inspiration, but they did not become part of the book. There was one, however, that I would like to share in my first post, as its power and poignancy I have never forgotten. My correspondent (I will call him Dan) told me that his father had recently died and been cremated. Dan had his father’s cremains at home with him and was pondering how best to honour his Dad’s memory. He settled on a plan to take a portion of the ashes to Germany. You see, Dan’s father had never known his own Dad. Dan’s grandfather had been a “bomber boy” with the RCAF in 1944 and had left behind his wife and yet-to-be-born child in Canada to head overseas. He had been shot down and killed over Germany and was buried there. Dan wanted to finally reunite, in some way, the father and son who had never met. I am sure you can see how stories like these inspired me to carry on with my project. Thank you again for reading, and I hope you will join me in future, as I share many stories that I was unable to include in the book. Future topics will include “Sweetheart” jewellery, escape and evasion photos, bum compasses, George the autopilot and a story about “wakey-wakey” pills. I would love to hear from you if you have any comments, suggestions, reviews or questions!

The Job To Be Done is scheduled to be published in January 2023. All the best to you and yours, Clint |

AuthorClint L. Coffey is the author of The Job To Be Done, available now through FriesenPress. Check back soon for new blog posts Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed