|

I know there are many of you (hah!) who are hoping for another controversial diatribe about current events, but I must disappoint you: I think I ruffled enough feathers in June’s blog, and will return to safer ground this month. June 6th of this year was the Eightieth Anniversary of D-Day, and it got me to thinking about anniversaries and my Dad and the rest of the Coffey crew. Eighty-two years ago today, on July 19th in 1942 Dad was a Leading Aircraftman 2, the lowest form of life in the Air Force, and was walking the perimeter at the No. 2 Air Observer School in Edmonton, on guard duty. A year later on July 19th 1943 Sgt. Coffey was overseas at the Pilot’s Advanced Flying Unit in Shropshire, flying a solo training exercise in an Airspeed Oxford. Finally we come to July 19th 1944, and we find Dad (a Flying Officer now) and crew in the thick of things, taking part in an intense battle known as Operation Crossbow. In 1943 odd installations began appearing all over the Pas de Calais and Dieppe areas of Nazi-occupied France, built by the Germans in preparation of their V-1 flying bomb offensive. The installations were launch facilities, and they were relatively small, consisting of a concrete launch ramp that pointed toward London, and several storage bunkers, shaped like a snow ski lying on its side (the curve in the bunker prevented rockets from fighter-bombers being shot up their length...). They were usually hidden in orchards or fields, scattered about the French countryside and they could be quickly built and were easy to repair. Dozens and dozens of the sites were built and they began firing their flying bombs in early June, just after D-Day. The V1’s were true terror weapons, as they could not really be aimed – they flew off towards London and an internal mileage counter would cut off the fuel and cause them to plummet to earth when they were over the city. Hitler hoped that hundreds of V-1’s falling on the London area every day would force the Allies to come to terms with him and make peace. What he got instead was an all-out offensive aimed to destroy his new wonder weapon. A defensive shield was placed across southern England, consisting of flak batteries and barrage balloons. Spitfires that had been specially modified to increase speed flew patrols in front and behind the screen, intercepting as many of the “buzz bombs” as they could. The strategic and tactical air forces of both Britain and the U.S. did their part as well, with ground attack fighter-bombers like the Typhoon and Thunderbolt pummelling the sites from low level with bombs and rockets, medium bombers like the B-26 Marauder attacking them in small formations and Lancasters and B-17’s staging heavy attacks when needed. All these attacks were part of what was dubbed Operation Crossbow. The Coffey crew took part in over a dozen attacks during Crossbow, and one of them was eighty years ago this very day, at about 4pm on July 19th, 1944. Dad’s logbook records the site they were attacking as “Rollez”, but the site was not actually in that tiny French village, but hidden in the woodland and pastures nearby. Other sources refer to the site as Verchocq, Bellevue or Herly, which are all very close by, within a kilometre. The bombing method used that day was to lead the 50 Lancasters to the aiming point with an Oboe-equipped Mosquito. Oboe consisted of a pair of radar beams broadcast from two stations in England – the specially equiped Mosquito followed one beam and when it intersected the second, dropped its target indicators on the aiming point. The Lancasters following closely behind would wait a second or two and then drop their loads in unison. It worked very well, and on this day there was minimal cloud, so they got a visual on the site as well. There were too many launching sites in Normandy for the Germans to defend effectively, and Dad and his comrades faced no opposition, either from flak or fighters. The Rollez site had been hit the week before, but the damage had been repaired and it required this second visit. The USAAF sent a photo recon P-38 aircraft over the site in mid-August and confirmed the site was destroyed and no further attacks were required (see below). Between the defensive screen in the south of England the Operation Crossbow offensive, Hitler’s “vengeance weapon” was prevented from making a significant impact on the course of the war, although it killed thousands of civilians and cost the lives of hundreds of bomber crews. Today the remains of the V1 site at Rollez are still prominently visible among the trees and pasture of the French countryside, jutting out of the ground like disinterred bones in an ancient graveyard.

0 Comments

It was never my intention with this blog to vent about current events or controversies in the world – the purpose was to present ideas and stories directly related to Bomber Command and my Dad’s service in that Second World War campaign. However, in recent months I have increasingly seen a convergence of the past and the present, of history repeating itself yet again. I can’t ignore the parallels I see.

On October 7th last year the world witnessed an attack on innocent civilians that rivalled anything committed by the Nazi’s in World War Two, if not in scale then certainly in the level of monstrous savagery. The atrocity committed during that dark day was, I am convinced, coldly calculated to elicit exactly the response it got. The terrorist group responsible for the sickening crimes scurried like rats back to Gaza, taking many of their victims (both dead and alive) with them, retreating into their maze of underground tunnels and leaving their women and children above to take the brunt of the response from Israel. It is worth noting that the Nazis built tunnels and concrete shelters as well, but they put their civilians into them to protect them from Allied attacks, leaving their military above to fight the enemy. And what was Israel to do then? Shake their fists impotently at Gaza and say “darn it, they got away! Oh, let us hope they don’t do it again!” The perpetrators of the October atrocity knew exactly what was coming and, I think, planned for it. The innocents who have died since then are just necessary sacrifices in their cruel, twisted view. And so, like a wounded wildcat who has been backed into a corner, Israel has unleashed everything it has. With a cowardly enemy who relishes hiding behind civilian shields the results have been horrific and heartrending – no one can deny it. Again: what was Israel to do? The parallels with the Bomber Campaign cannot be avoided for anyone, who like me, has a passion for history. The RAF and the USAAF attacked Germany with single minded ruthlessness, with all the weapons available to them. If an area of a city had to be destroyed in order to destroy Hitler’s factories then so be it – and if the bombs flattened homes and killed the civilian workers who ran those factories so much the better. Heartless and cold, but if the Nazi empire was to be defeated, necessary – the gloves were off, this was a fight for survival. This is why no one should start a war, and why the moral responsibility for innocent deaths should be laid at the feet of those who started it. During and after the World War Two, the criticism was constant – accusations that Bomber Command had gone too far, that the brave young men of the RAF and USAAF had taken part in “war crimes” ... “never mind Coventry and Dachau, remember Dresden!” the post-war pundits cried. Like the soldiers of the I.D.F., the airmen of Bomber Command were given the thankless task of taking the fight to a cruel, fanatical enemy who could not be separated from the civilian population. After the war the Bomber Campaign was condemned by some for the devastation it had wrought in the process of defeating the most evil regime in history. Well, I for one have lost patience with the Monday morning quarterbacking, the unfair criticism, the condemnation by those not there, the accusations of war crimes – I stand with the “bomber boys”, and by the same token and for the same reasons I Stand With Israel. My Dad is the main character in The Job To Be Done but I wish I had been able to tell more of my Mom’s story in the book, as she play an undoubtedly vital role in the story. My Dad’s love for her and his desire to return home safely to her and his young son Gary (my eldest brother) motivated some of the decisions he made (and attitudes he had) while he served overseas in 1943/44. I didn’t tell more of Mom’s life at that time simply because I don’t know a lot about it – to my discredit I never asked her while she was alive and now the history is sadly lost.

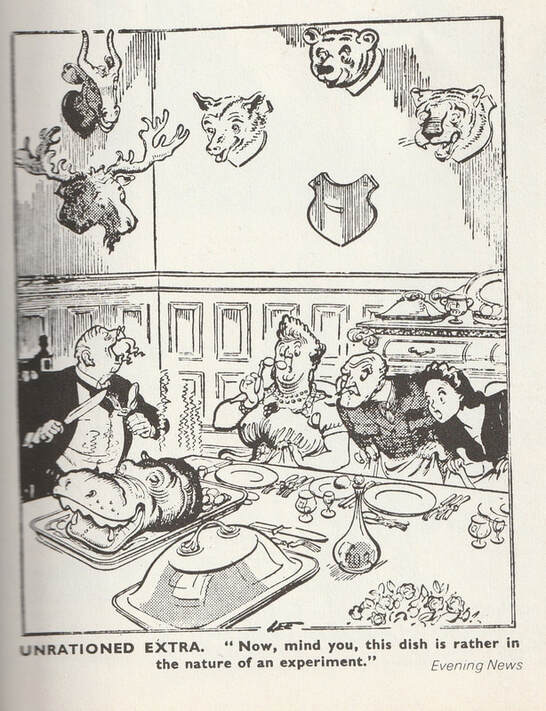

The bare basics of her story are similar to millions of other mothers during the Second World War – she carried on without her husband, doing whatever was necessary to provide for her son and keep “body and soul” together until he returned. If he returned, that is...she must have dreaded every day he was away that a telegram would arrive with the awful news that Dad was “missing – presumed killed”. With losses running at 50% in Bomber Command this was a very real possibility. Mom lived in the small town of Provost Alberta and worked for a time at the local hotel, and rented a large house where she could sub-let rooms to other young women. She made do, scrimped and saved, did what was required without complaint and found time every month to send a care package to my Dad, filled with small gifts like Canadian cigarettes, hand-knit socks and chocolate, each item carefully and lovingly gift wrapped. This supportive lifeline from home was, I believe, influential in shaping my Dad’s time in Bomber Command. His attitude of serious attention to details and his professionalism might have been different if he had been a single man without a family to think about. His decision to join the Pathfinder Force meant getting home a year sooner than had he stayed in a regular squadron – he accepted the increased risk in return for that chance of getting back to Mom and Gary sooner. Moms in Great Britain had it even tougher than those in North America, with acute shortages of everything from sugar to trousers. The watchwords for every British mother were “make do and mend!" (see cartoon above) as British clothing factories were busy turning out uniforms and parachutes, not civilian clothing. One story in particular comes to mind when I think of mothers taking charge and getting the job done while their husbands were far away. My friend Henry was a youngster during the Second World War and grew up in the small town of Rochdale, near Manchester. Henry’s Dad join the British Army in 1940 and served during the Fall of France when he was evacuated at Dunkirk. Later he took part in the invasion of North Africa (Operation Torch) and fought his way across North Africa against Rommel’s Afrika Korps. By 1944 he was a Sergeant Major, leading his men in savage fighting up the boot of Italy. After four years of almost continuous absence, Sergeant Major Calladine was finally “demobbed” and returned to his home, which had been kept running and safely intact by Henry’s beloved “Mum”. Collapsing into his armchair, finally home again, Henry’s Dad noticed one big change he felt compelled to comment on: “Bloody hell, when did we get a cat?!” In honour of the strength and courage of my Mom and all other moms, here is a photo of Mrs. Ruby Coffey and Gary, taken in 1944 while Dad was thousands of lonely miles away. I recently finished reading a fascinating and unique book entitled Thinks He’s A Bird, by Australian author Brian Campbell. It is the story of a young Aussie named Keith Watson who joins the R.A.F. in 1942 and eventually ends up as the captain of a Lancaster bomber in the Pathfinder Force. Watson kept extensive journals and sent numerous letters, all of which survived and were combed through by the author to create a remarkable narrative about a young man at war, far from home. Watson’s eye for detail and Campbell’s skilful weaving of the story make for fascinating reading. One detail of wartime life that Keith Watson often comments on is food, an interest we all share. Second World War rationing in Britain is a fascinating subject – as I was researching my Dad’s time in Bomber Command I often wondered, “what was he eating and drinking...?”

Wartime rationing in Britain meant everyone had less to work with. Brewers had to make due with less sugar, so wartime beer was lower in alcohol than in peacetime – but it was never rationed. Lord Wooton, Churchill’s Food Minister, said “..if we are to maintain at least some semblance of normal life, beer must be produced...”. Hear, hear! In the words of Mark Twain, beer is proof God loves us and wants us to be happy. During the Battle of Britain the country’s beer brewers even had a hard time getting hops, as it was hazardous for the pickers to work in the fields of Kent with the battles raging overhead. Anti-aircraft shrapnel and expended bullets from Spitfires and ME-109’s would have been raining down like lethal hail that summer of 1940. Coupon ration books were issued to all, to control consumption (but of course the black market thrived) and everything from candy to lard had a weekly allowance. Everyone scrimped and saved and made due with what was available. The Ministry of Food published a weekly edition of “Food Facts” which gave tips like “Never waste the peel and cores of your apples. Boil them with a little sugar in water and you’ll have a delicious and very health-giving drink”, and “Try young nasturtium leaves instead of jam at tea-time. It makes a change; it’s better for you and saves the country’s sugar”. The wartime cartoon reproduced above sums up the attitude of the times very well. People were allotted one egg a week, and many made do with powdered eggs, which were coming from the U.S.A. by the ton. The boys of Bomber Command were lucky in this regard – it became tradition for them to be served fresh eggs, bacon and chips on days when they were flying an operation. Meals on the airbases were spartan. Bob McWhirter, the Coffey crew’s rear gunner, told me in 2015 that he remembered a lot of mutton and cold, clammy noodles were on offer. After he and the rest of the crew reached officer rank the food improved a bit, served with a “bit more imagination”, although there was still only so much the station cooks could do with the limited ingredients they had available. However disappointing a meal may have been at a Bomber Command base during the Second World War, the “brylcreem boys” (as the Army nicknamed them) had it better than British and Canadian troops in Normandy after D-Day. The soldiers there lived on “compo rations” for the most part. In his book Caen: Anvil of Victory, author Alexander McKee relates the story of a hungry British soldier who turns down an offer of a hot meal during the thick of the fighting – the meal presented was “P.V.” (canned pork and veggie stew), a dish “so vile” even “a dog” wouldn’t eat it. One of the stories in The Job To Be Done is told in increments – I thought it was appropriate to tell it that way, as it is the way I learned the full story, a bit at a time over several years of research. The story is that of the crew’s mid-upper gunner, Ken H., who had accidentally fired a burst of machine gun bullets into the rear turret of his own aircraft, killing his own tail gunner. The accident had happened a year before he joined my Dad and crew, and Ken had kept the details to himself until the Coffey crew finished their tour of operations, and then confessed the details to his friends (including the fact he had been court-martialed and grounded) before they all parted ways.

One aspect of the story eluded my sleuthing skills – I was never able to find the actual transcripts of Ken’s court-martial. In the book, I posit that perhaps the records were still in a file box somewhere in Kew, where the U.K. stores original historical records. It turns out they are online, it is just a matter of knowing where to look, and having contacts online who keep you in mind when they run across something they think you might find interesting (....thank you again Dave). Ken H faced a court martial several months after the accident happened, and the transcripts tell the tragic story of a perfect storm of mistakes, sloppy leadership and faulty training. The whole story of the accident is told in detail in The Job To Be Done, but suffice it to say that Ken experienced a jammed gun while on an anti-submarine patrol (flying out of RAF Beaulieu in Hampshire) and in the course of clearing it had accidentally fired a small burst. The errant bullets had torn into the rear turret of his Halifax bomber and mortally wounded his own tail gunner. As I read through the transcripts, I was struck by how thorough, fair-minded and professional the hearing was. Everyone from the Medical Officer who gave the wounded rear gunner first aid to the armourers who serviced the .303 machine guns was spoken to at length, and both the defence and prosecutor were professional lawyers, serving with the R.C.A.F. Ken himself was given full opportunity to tell his side of the story, and he comes across as honest and without guile. The story that emerged from the testimony is heartbreaking – as crazy as it sounds, the powers-that-be had sent Ken into combat on his very first operation, having never operated a mid-upper turret before. All of Ken’s training at Air Gunner’s school, the Operational Training Unit and the Heavy Conversion Unit had been completed in the rear turret only. A number of factors collided to result in confusion and assumptions. Ken’s Squadron had only just arrived at RAF Beaulieu, having moved in a frenzy, lock, stock and barrel, from RAF Topcliffe in the Midlands. In the chaos of attempting to get the Squadron back into operation as soon as possible things had been missed and questions had neglected to be asked. No one in the Squadron, not the Gunnery Officer, not the Flight Commander, not even Ken’s new pilot had asked if the new Air Gunner had any experience in the mid-upper turret of a Halifax, a lapse in leadership I find a bit shocking. Ken, no doubt gung-ho, confidant and not wanting to appear hesitant, had not volunteered the info. It is understandable – he was young, enthused, and was, after all, a fully qualified air gunner, having completed all his training. The Air Gunner’s Book (the bible of all the do’s and don’ts of the Halifax gun turrets, something every gunner at an operational squadron was made to read and sign off on) was missing from the Squadron – no one knew why. In the upheaval of the move from Topcliffe to Beaulieu, many things got missed and misplaced. The pressure was on the Squadron to get up to speed and back in operation after their move, to start their anti-submarine patrols and try to stem the losses that Hitler’s U-boats were wreaking on Allied shipping. So on a fateful November morning, Ken and his crew took off to begin their first combat patrol, searching for any signs of submarines in the Bay of Biscay. When Ken encountered a jam in one of his Browning machine guns it seems he got tunnel vision and, by force of habit, turned his turret to face the rear of the aircraft, as he would normally do in a rear turret. He then operated the gun manually, so that only the single problematic gun would fire and clear the jam. Tragically, in doing so he bypassed the safety mechanism that prevented the guns from firing if they were pointed at any part of the aircraft. Two mistakes, done in haste – neither would have been mistakes if he had been in the rear turret. But he was in the mid-upper, and the mistakes cost a man his life. Even the prosecutor seemed sympathetic to the way Ken had been set up to fail, asking the judges to take his inexperience into consideration. In the end, Ken was convicted, demoted and taken into custody. After his sentence was done, he was reinstated to his previous rank, and, displaying remarkable character and courage, volunteered once again for aircrew duties. He joined my Dad and crew in February of 1944 and became a vital and skilled member of a successful Bomber Command aircrew. Years ago I had a neighbour who was originally from the U.S. and who had a big pickup truck with a canopy that was boldly emblazoned with decals detailing his service in Vietnam. USMC VIETNAM WAR VETERAN it proclaimed in big white letters, along with the names of battles (KHE SAHN etc) and colour reproductions of all the campaign ribbons he had earned. I never spoke to the fellow, as he had a bad reputation in the neighbourhood for reasons I won’t go in to, but what struck me about his display was how foreign it was to my own experience with my Dad’s service. My Dad (and every other Second World War veteran I have read about or spoken to, almost without exception) was modest and went out of his way not to appear to be “talking up” his wartime service. The difference between Dad’s attitude and my neighbours could not be starker. The thought of my Dad driving around in a truck proclaiming RCAF BOMBER COMMAND VETERAN - NUREMBERG – BERLIN – DISTINGUISHED FLYING CROSS etc etc is laughable. Was it his belonging to an earlier generation that accounted for the difference in attitude from my neighbour? The type of war he fought in? The culture he grew up in (Canadian vs American)? I am not sure.

The attitude of British and Commonwealth servicemen towards the medals they were awarded is a case in point. Decorations were universally referred to as “gongs”, and the Distinguished Flying Cross was known known to Bomber Command airmen as the “Survivor’s Gong” - in other words, it was often a reward for having actually survived a tour of operations despite the atrocious loss rates (topping 50% or more). I never knew my Dad had gotten a medal until I asked him specifically, when I was about 14. Bob McWhirter (the rear gunner in my Dad’s Lancaster crew) had his D.F.C. hidden in the back of a drawer – his family found it when they were moving house years after the war’s end. Teddy Rutherglen (the Wireless Operator on Dad’s crew) kept his D.F.C. tucked away as well – he was moved when his teenage daughter found it and had it framed as a gift..."I didn’t think anyone cared” he told her, fighting back tears. The modesty and humility of that generation, I have learned, are signs of confidence and inner strength, and of an understanding that one has been very, very lucky – and that many of ones friends and comrades were not. At the end of the Second World War, Bomber Command was snubbed by Winston Churchill, who gave no mention of them (or their leader, Sir Arthur Harris) in his Victory Speech, and no special campaign ribbon to acknowledge their contribution in defeating Hitler. Seventy years later the Canadian government came out with a Bomber Command clasp (to be placed on the 39-45 Aircrew Europe campaign medal) to honour Canadian bomber crews, but the timing was somewhat suspect. The government of the day was getting well deserved criticism for its poor treatment of Canada’s Afghanistan veterans, and many felt (including me) that the clasp was bit of a publicity stunt to show solidarity with veterans. It was a bit of a “too little, too late” situation for many. Despite my misgivings, I eventually did apply for the clasp on behalf of my late father. That was about 18 months ago – no word yet... I related in The Job To Be Done that I have experienced frustration and annoyance on many occasions since I started the research into my Dad’s time in the R.C.A.F.

The source is always the same: misleading and downright sloppy “documentaries” related to the Bomber Campaign during the Second World War. In my book I specifically mention Death By Moonlight, a deceptive film by the N.F.B. from the 1980’s, which caused protests from outraged veterans in Canada upon it’s release. I have watched dozens of YouTube videos over the years, and some have been fair and accurate and some have regurgitated outrageous nonsense. You would think that big budget network documentaries would have higher standards than a random YouTube video, but it is often not the case. The most recent encounter I have had with a documentary that caused me to want to throw a coffee cup at my TV was Netflix’s WW2: From The Front Lines. The visuals in this mini series are stunning, there is no doubt about it – the colourizing of the original black and white footage is masterfully done. What had me frothing at the mouth was the way the producers handled the Bomber Campaign, basically disparaging it with misinformation and misleading commentary. The narrator explains that precision bombing was beyond the capabilities of Bomber Command, so the British answer was “to find easier targets”. Libellous nonsense. The producers scoured the archives and managed to find a 30 second clip of a Canadian veteran expressing remorse that he and his friends were sent to bomb Hamburg. The emotion and sincerity of this aging warrior is beyond question, his words help us understand the terrible pressure the young men of Bomber Command were under, but such sentiments don’t change the facts. Portrayals of raw emotion can be an important part of any documentary, but they have to be balanced with factual analysis. To add to the slander, the narrator concludes the portion on the Bomber Campaign by implying that the bombing of Hamburg actually hurt the Allied cause by increasing the numbers of young German men joining the armed forces! That is so nonsensical that it gave me a headache when I heard it. Germany had been a military dictatorship under Hitler’s iron rule for 10 years by 1943 – the idea that there were pools of able bodied young men sitting around, three years into the war, waiting for the proper motivation to join the Wehrmacht is laughable. Four months previous to the Hamburg attacks, Josef Goebbels had made his infamous Sportspalast speech, in which he told the German people that what they were engaged in was “total war”. Despite the fact that I think the producers of From The Front Lines should be ashamed of the sloppy work they did, I actually recommend watching the series, as the visuals are breathtaking – just make sure you take a healthy grain of salt first. As an antidote to this nonsense about the Bomber Campaign, I heartily recommend Bomber Boys, a BBC production by the McGregor brothers – stirring, inspiring...and factual. My Dad was overseas for almost two years, but the way the timing worked out he only spent one Christmas away from Canada, leaving Halifax harbour in May of ‘43 and arriving home on Xmas day 1944.

As luck would have it, he and his four crewmates (Bob McWhirter, Bob Bayne, Malcolm Dingwall and Teddy Rutherglen) would spend their only Christmas Day overseas in about the worst spot imaginable for an RAF bomber command crew, short of a POW camp. Not at a squadron Sergeant’s mess, warm and cozy among friends, with beer and music. Not on leave at a comfortable hotel in London. No, as luck would have the Coffey crew were at Battle School in the lonely Yorkshire Moors (at RAF Dalton) in December of 1943. As related in The Job To Be Done, Battle School was a sort of four-week long commando course, where aircrew would learn escape and evasion techniques and practice hand to hand combat. Most thought it was a waste of time, but pretty much every RCAF aircrew took part in it, it was one of the components of their training deemed essential before commencing operations with a front line squadron. December on the Yorkshire Moors was wet, cold and dreary, and the Battle School records relate that the buildings were so cold students were burning anything they could get their hands on to try and warm up. They spent their days charging about the Moors in the rain, staging mock attacks and thrusting bayonets into straw dummies. As Christmas Day approached, I am sure many of the young Canadians grew morose with thoughts of home and loved ones far away. About 17 miles away from Dalton, also training on the Yorkshire Moors, were two battalions of Guards, stationed at Duncombe Park. The 1st Armoured Battalion Coldstream Guards and the 2nd Armoured Battalion Irish Guards were originally trained as infantry, but were now learning to fight with Sherman Tanks instead of rifles in preparation for the Normandy invasion. The two units had been at Duncombe for months (and therefore likely had better “connections” for food and beverages than the RCAF airmen) so I am betting their mess was comfortable and well stocked. The commanding officers of both Guards units kindly invited any of the airmen at Dalton who did not have anywhere to go to come and visit them at Duncombe for Christmas Day. It was a kind offer, and well over a dozen young Canadians (and one Kiwi) accepted the invitation according to the Battle School records. All the young airmen enjoyed their day, remarking upon their return about the warmness and hospitality of the British tankers. I am betting that rides on the Guards new Sherman tanks were part of the festivities, as well as food and drink that was likely a big step up from what was on offer at the Sergeant’s mess back at RAF Dalton. None of those attending knew it, but I’ll wager that some of them were to “meet” again, far away and in much different circumstances. Eight months later, in July of 1944, both Guards battalions were in the thick of the fighting in Normandy, locked in savage combat with the Waffen SS, who had been ordered by Hitler to defend every foot of Occupied France to the death. Bomber Command was tasked on many occasions that summer with assisting the Army by pummelling German defences. It was a risky undertaking, with Canadian and British forces often only a few hundred yards away from the aiming point. Dad and his crew took part in many of these attacks at places like Villers-Bocage, Caen and Falaise. I like to think that maybe at some point some of the lads who hosted Dad and his friends that Xmas dinner might have looked up at the sky from their Sherman tanks and cheered the Lancasters on as they made their bombing runs on the Tigers and Panthers of the Waffen SS. A flight of fancy on my part perhaps. I wish you all a wonderful Christmas season. I am not a Christian, but as we look at tragic events around the world, from Ukraine to the Middle East, I hope we can all agree with Jesus when he declared “Blessed are the peacemakers”. As November 11th approaches again, I am again faced with the same internal conflict. The problem is that I know I am going to have to run across that disturbing poem In Flanders Fields again. I have no idea why Canadians find it’s jingoistic, pro-war message so compelling – I can only assume that most have never read the whole thing, as it is often just the one stanza about poppies that is quoted. I am equally appalled by the often repeated idea, regularly heard around Remembrance Day, that the battle of Vimy Ridge was somehow a glorious victory for Canada. On the contrary, it seems to me that it was a pointless slaughter, and thousands of Canadian families lost loved ones for a cause that was unworthy of their sacrifice. Machine guns and barbed wire were two horrific weapons that had been invented decades before 1914, but the fat, smug, cigar-smoking generals and politicians were too myopic to see what their implications were for modern warfare, and were happy to embark on an exciting new war filled with, they assumed, cavalry charges and glory. Instead, what they sent their millions of young men into was a slaughterhouse of mud and trenches.

For anyone who wishes to read a real war poem, one which punches hard in telling it’s tale of courage, horror and camaraderie, I recommend Wilfred Owen’s Dulce et Decorum Est. Owen, who served in WW1 and died fighting in it, paints a savage picture, and it is a poem that I cannot read aloud without choking up. And here we come to the source of my internal conflict. Can we question the cause that veterans fought for, as I have just done with the First World War, without disrespecting and dishonouring the memory of those brave young men? I sincerely hope so, because I think we should always question and question again the cause we are sending our young men and women into harm’s way for. They deserve nothing less. I am grateful that Canada declined to participate in George W’s invasion of Iraq in 2003 – had we done so we would today be mourning god knows how many more Canadian youth on Remembrance Day. And for what? Our Second World War veterans sacrificed so much...so many gave their very lives, but the cause was noble and worthwhile. They were not just fighting and dying for their country, they were fighting to save civilization itself, to put an end to a monstrous evil. Families who lost loved ones could at least take some comfort in that. For Remembrance Day I offer a poem you likely haven’t heard before. It was written by an ex-Bomber Command aircrew named Roy Collins, who served with 90 Squadron in WW2. The poem is included in a wonderful book of Bomber Command poetry entitled These Are But Words. Mr. Collins’ poem is titled Never Go Back, They Say. It is painfully poignant, honest and it doesn’t glorify war. Never Go Back, They Say I went back to the old field At the close of an Autumn day. To find the tower crumbling, The hangars filled with hay. The dead leaves swirled and eddied And crunched beneath my feet. This concrete base, complete with plough, Was once the gunner’s hut. What could it be, what was it That I had come to find? Traces of my vanished youth, or was it peace of mind? The shadows darkened, lengthened, As I slowly strolled around, Stood and looked and listened As they crept along the ground. And then I heard – or did I? A faintly mocking laugh, The tinkle of a spanner, The chuckle of a WAAF. The muted sound of Merlins, throttles eased by ghostly hands, Screech of tyres on tarmac, The lost coming in to land. For here were ghosts in plenty, Young ghosts of yesteryear, But I am young no longer And am not wanted here. I went back to the old field At the close of an Autumn day. I wish to god I’d listened, And I had stayed away. My wife and I recently returned from three weeks in Portugal, a country I had never visited before (as an aside, it is an amazing place with incredible food and rich history – well worth a visit!). One thing that did strike me as odd about Portugal though, was the lack of Second World War history. The country’s dictator, Salazar, kept Portugal out of the war, sitting on the fence until it was clear who was going to win, and then giving the Allies use of the Azores Islands as an air base late in the war. I only saw two military monuments during our time in the country, one commemorating Portugal’s contribution of a battalion of infantry to the Allied cause in WW1, and the other to the country’s losses in its colonial wars in Africa. In contrast, I have travelled throughout the U.K., and there is hardly a village without a cenotaph memorializing local losses in both World Wars.

The lack of Second World War awareness hit home to me even more one evening in Lisbon. Our guide, a friend of the couple we were travelling with who lives part-time in Lisbon, took us to an amazing little bar in the old part of town, one famous for its collection of 20th century memorabilia. The place had a plain, nondescript frontage on a side street, and you had to ring the doorbell to be let in by staff – I would have walked right by it had it not been for our guide. Inside was like Aladin’s cave – every wall was covered in glass-fronted cases absolutely jam-packed with bric-a-brac of every description. Dolls, toy soldiers, model airplanes, signage, hats, helmets, toy cars, swords etc etc....it would take days to look at every item. As I sat with my glass of vintage Port my eyes were drawn to one wall in particular, as it was filled with Nazi memorabilia. Officer’s hats, helmets, sashes, small banners and the like, all prominently adorned with the swastika. Such a display would be unthinkable in Canada, the U.K. or most other Western democracies I would think. The last time I had seen real Nazi relics had been in the Imperial War Museum in London forty years previously. The display didn’t offend me, but I would be dishonest if I didn’t admit I found it disconcerting. Very soon after arriving home, the firestorm surrounding Mr. Hunka, the Ukrainian WW2 veteran, erupted across Canada. Mr. Hunka was honoured with a standing ovation in Parliament, but it was soon revealed that the unit he had served in during the war was none other than the Waffen SS, Hitler’s elite troops, who had committed a plethora of atrocities from 1939-1945. I was outraged at first, but in an interesting coincidence, I had just finished reading Anne Applebaum’s book Red Famine, about the genocide perpetrated on Ukraine over the course of some 20 years by Josef Stalin. Was it any wonder that many Ukrainians looked upon the invading German army as liberators? Is Mr. Hunka any different from the 100’s of German scientists that the U.S. brought to America after the war to spearhead the missile and space program? Many of them were actual Nazi party members after all, and I haven’t heard anyone say that Mr. Hunka was as well. I am no apologist for the Waffen SS - far from it - and it is outrageous that he was honoured the way he was (the Waffen SS was officially designated a criminal organization at Nuremburg, and its members all swore a personal oath of loyalty to Hitler), but does serving in that unit automatically make one a “Nazi”? I am conflicted...in part because I am pretty sure I know what my Dad and the rest of his aircrew comrades would say! If writing The Job To Be Done has taught me one thing, it is that studying history requires a nuanced approach – often a simple “a Nazi is a Nazi is a Nazi” approach results in a comic-book level of understanding of our rich history. |

AuthorClint L. Coffey is the author of The Job To Be Done, available now through FriesenPress. Check back soon for new blog posts Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed