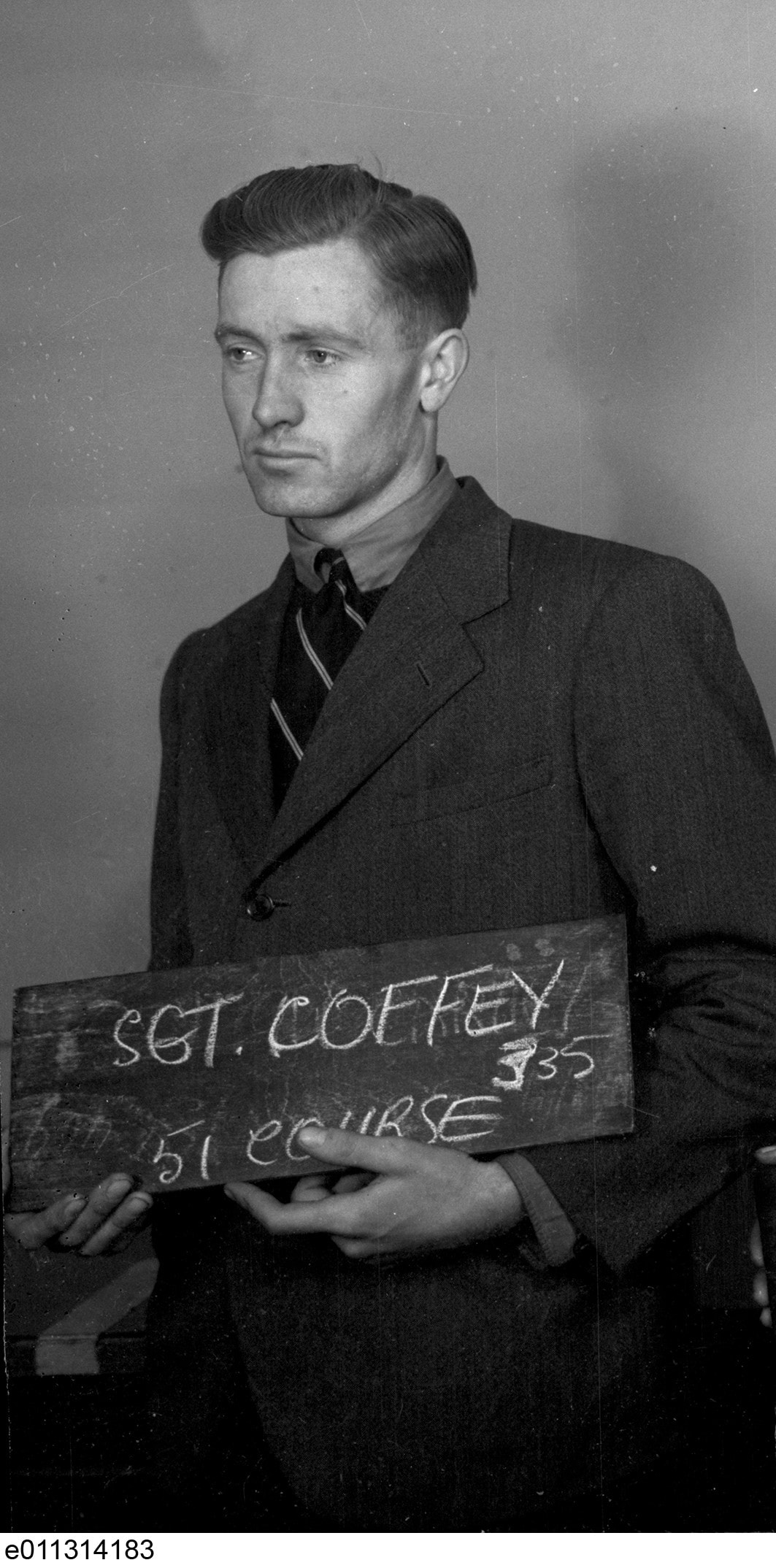

Six tiny black and white “headshot” photos of my Dad have, in an odd way, bracketed my time as the temporary caretaker of my Dad’s WW2 memorabilia. Four I inherited in 1990 (shown above) when Dad passed away and two arrived in my email inbox just last week, just days after The Job To Be Done was finally published. These mugshots, taken around the same time and location, and for the same purpose, took eighty years to be reunited in my files. The two I received recently I had worked hard for – I had seen the tiny 35mm negatives among the hundreds of pages of scanned documents that the Canadian government had sent me when I requested Dad’s service records. Only the negatives were shown – I could tell they were of a man in civilian clothing, but I would not have known for sure it was Dad if he hadn’t been holding a sign, helpfully reading “COFFEY”. See below. At any rate, a year or two after first seeing the negatives, I decided to ask the Library and Archives Canada if it would be possible to get them developed and sent to me. It turned out that it was, although due to the Covid pandemic the bureaucratic wheels turned very slowly. They finally arrived last week, and they are delightful. All six of the photos are examples of escape and evasion photos. You can see in one that the chalkboard Dad holds says “51 Course” - this indicates it was taken at the No.22 Operational Training Unit, which Dad and crew attended in September 1943. During the course of the War, hundreds of allied aircrew who had been shot down were able to evade capture, connect with the local resistance and eventually make their way back to England. The numbers were small compared to those who were killed or captured, but it is still an amazing story. To improve the chances of those who found themselves alone in enemy territory, each airman was issued with a pocket-sized escape kit. This usually consisted of items like silk maps, chocolate bars, a tiny compass, some Benzedrine tablets (“wakey-wakey pills”) to boost energy, some local currency and a set of tiny passport-style photos, taken in civilian clothing. Should a downed airman be lucky enough to make contact with the local underground, this last item could be used by their experts to make fake identity papers. My Dad looks exhausted in all the photos, especially in the one I just received. It’s not surprising: by September of 1943 when the photo was taken, he had been undergoing near-constant (and often dangerous) training for over a year. He had said goodbye to his family, not knowing whether he would ever see them or Canada again. He had crossed the ocean to a faraway land, without a friend, and had been posted into one strange, challenging environment after another. It is no wonder there are bags under his eyes! As always, thank you for reading.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorClint L. Coffey is the author of The Job To Be Done, available now through FriesenPress. Check back soon for new blog posts Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed